“Isis: “Give heed, my son Horus; for you shall

hear the secret doctrine, of which our

forefather Kamephis was the first teacher.

[…]

I heard it from Hermes,

the writer of the records,

when he initiated me

in the rite of Black (Perfection).”

Words of Isis from the sacred book

of Hermes Trismegistus entitled Kore Kosmu ).*

“For Trismegistus who, I do not know how,

has completed the discovery of virtually the

entire truth, has often described the power

and the majesty of the Word, as illustrated by

the foregoing quotation, where he (Hermes)

proclaims the existence of an ineffable and

holy Word, whose pronunciation is beyond

the power of man . . .”

(Lactantius, Divinae institutiones iv, 9,3)

“For the gate is narrow and the way is hard,

that leads to life, and those who find it are few.”

(Matthew vii, A)

* (“The Virgin of the World’“); trsl. Waller Scott, Hermetica, vol. i, Oxford, 1924. p. 457;

Our anonymous author concludes Letter VIII with this reference linking Justice to The Hermit:

“Justice, the practice of the balance, is only the beginning of a long path of the development of conscience —and therefore of the growth of freedom. The following Arcanum, the Hermit, invites us to a meditative endeavour dedicated to the path of conscience” (196).

ThirtyThree pages later, he concludes the letter on The Hermit with this observation:

“The Hermit of the ninth Card is the Christian Hermeticist who represents

. . . the work of realizing the supremacy of the heart in the human being . . . “the work of salvation” — because the “salvation of the soul” is the restoration of the reign of the heart” (229).

Let us then give due diligence to what follows that we might realize the supremacy of the heart and that the reign of the heart might be restored in us and in our sphere of influence.

The Hermit as a source of inspiration in our youth… [199-200]

The letter opens with an effusive tribute to “the venerable and mysterious Hermit” who is said to be “the master of dreams” for young idealists regardless of where they live and regardless of whether this “prototype of the wise and good [spiritual] father” appears to them in the form of a Russian staretz, a Hassidic tsaddik, or an Indian chela or guru. Examples suggested from the Christian tradition include Origen, Clement of Alexandria, St. Dominic, St Francis of Assisi, and Ignatius of Loyola. Reference is also made to Socrates, Plato, and Zarathustra, as well as a more general reference to the Jewish prophets and ascetics.

The basic description and symbolism of the Hermit… [200-201]

The letter continues with this very basic description of the symbolism of the Hermit which will inform each of the remaining segments of the letter:

“[The Hermit] possesses the gift of letting light shine in the darkness—this is his “lamp”; he has the faculty of separating himself from the collective moods, prejudices and desires of race, nation, class and family— the faculty of reducing to silence the cacophony of collectivism vociferating around him, in order to listen to and understand the hierarchical harmony of the spheres —this is his “mantle”; at the same time he possesses a sense of realism which is so developed that he stands in the domain of reality not on two feet, but rather on three, i.e. he advances only after having touched the ground through immediate experience and at first-hand contact without intermediaries—this is his “staff’. He creates light, he creates silence and he creates certainty—conforming to the criterion of the Emerald Table, namely the triple concordance of that which is clear, of that which is in harmony with the totality of revealed truths and of that which is the object of immediate experience:

Verum, sine mendacio, certum et verisstmum (Tabula Smaragdina, 1).

Verum, sine mendacio — this is clarity (the lamp);

Certum — this is the concordance of that which is clear and the totality of other truths (the “lamp” and the “mantle”);

Verissimum — this is the concordance of that which is clear, the totality of other truths, and authentic and immediate experience (the “lamp”, the “mantle” and the “staff”).“The Hermit . . . represents not only a wise and good father who is a reflection of the Father in heaven, but also the method and essence of Hermeticism. For Hermeticism is founded on the concordance of three methods of knowledge: the a priori knowledge of intelligence (the “lamp”); the harmony of all by analogy (the “mantle”); and authentic immediate experience (the “staff).

The three-fold synthesis of the Hermit:

-

- Idealism – Realism [201-204]

- Realism – Nominalism [204-209]

- Faith – Empirical Science [209-217]

Each of the bulleted items, above, represent an antinomy that has puzzled professional philosophers and arm-chair metaphysicians for many centuries if not millennia. An antinomy, in the philosophical sense, may be briefly defined as “a contradiction between logical conclusions” (etymonline.com). Less rigorously, it may just refer to a paradox.

Kant made this word famous with his treatment of four antinomies in The Critique of Pure Reason (and in his Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics). Below, for example, is the fourth antinomy, together with its resolution, as presented in The Prolegomena:

Kant made this word famous with his treatment of four antinomies in The Critique of Pure Reason (and in his Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics). Below, for example, is the fourth antinomy, together with its resolution, as presented in The Prolegomena:

Thesis: In the Series of the World-Causes there is some necessary Being.

Antithesis: There is Nothing necessary in the World, but in this Series All is incidental.

He concludes the section as follows:

“…provided the cause in the appearance is distinguished from the cause of the appearance (so far as it can be thought as a thing in itself), both propositions are perfectly reconcilable: the one, that there is nowhere in the sensuous world a cause (according to similar laws of causality), whose existence is absolutely necessary; the other, that this world is nevertheless connected with a Necessary Being as its cause (but of another kind and according to another law). The incompatibility of these propositions entirely rests upon the mistake of extending what is valid merely of appearances to things in themselves, and in general confusing both in one concept.” [see The Cause IN Appearances Vs. The Cause OF Appearances]

Each of The Hermit’s three antinomies are worth careful consideration and the first two, especially, should be required reading for every student of philosophy.

1. Idealism – Realism [201-204]

Our anonymous author summarizes this antinomy as follows:

1. The antinomy “idealism —realism”

This reduces to two opposite formulae, namely:“Consciousness or the idea is prior to everything”—this is the

formula of idealism; and

“The thing (res) is prior to all consciousness or ideas”—this is

the basic formula of realism.

The formula of realism falls short, he argues, because it make an idol of things–suggesting that the light of thought is merely the product of antecedent physical processes. The formula of idealism falls short, he argues, because it tends to make an idol of the human intellect (disregarding the Divine intellect which transcends it).

2. Realism – Nominalism [204-209]

In his discussion of this antinomy, our anonymous author first distinguishes the realism of this antinomy from the realism of the preceding one:

Now “realism”, as a current of occidental thought opposed to nominalism, differs from realism opposed to idealism in the sense that it is a matter here of the objective reality of universals (types and species) and not of the correspondence between notions of the intellect and the reality of objects (as the criterion of truth). Therefore it is a question of a totally different problem. “Realists”, in that which concerns the problem of the reality of universals, are in fact extreme “idealists” in that which concerns the problem of the priority of the intellect or the object.

The realism – nominalism antinomy, as he presents, is reducible to the following theses:

“The general is anterior to the particular”— is the formula at the

basis of realism.“The particular is anterior to the general”—is the counter-formula of nominalism.

Note, as indicated above, that the “realist” in this antinomy is an idealist (the idea is prior) and the nominalist is a “realist” in the earlier sense, inasmuch as the particular is prior to the idea. The difference between the two antinomies, however, is not merely one of semantics since the nominalist in this antinomy insists that general ideas are merely names and that universals, as such, do not exist (i.e. no two particulars are really alike . . . rather, we simply label them the same based on perceived similarities which– rather than reflecting our knowledge –actually reflect the limitations of our knowledge.) The “realists” in the first antinomy, while likewise asserting the priority of things, do not necessarily deny the reality of universals.

With regards to the realist in the second sense (as used in the second of the three antinomies), our anonymous author continues:

These two contrary theses imply that for realism the general is more real and of higher objective value than the particular, and that for nominalism the particular is more real and of higher objective value than the general. In other words, for realism humanity is more real and is of higher value than the individual man. In contrast, for nominalism it is the individual man who is more real and has a higher value than humanity.

For realism, there would be no human beings if there were no humanity. For nominalism, on the contrary, there would be no humanity if there were no human beings. Human beings compose humanity, says the nominalist. Humanity engenders, from its invisible but real womb, individual human beings, says the realist.

3. Faith – Empirical Science [209-217]

This antinomy calls to mind the much debated conflict between Faith and Reason as well as Kant’s famous decision to deny knowledge so as to make room for faith:

“I cannot even assume God, freedom and immortality for the sake of the necessary practical use of my reason unless I simultaneously deprive speculative reason of its pretension to extravagant insights; because in order to attain to such insights, speculative reason would have to help itself to principles that in fact reach only to objects of possible experience, and which, if they were to be applied to what cannot be an object of experience, then they would always actually transform it into an appearance, and thus declare all practical extension of pure reason to be impossible. Thus I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith” (BXXX).

The German word for faith, above– Glaube –is glossed by Jonathan Bennett as religious faith. But whatever Kant may have intended in that context, faith in the context of The Hermit— as the remainder of the letter makes clear –is much more than mere belief (construed in terms of intellectual assent or dogmatic profession). It is also much more than an intense emotional experience or “personal feeling” (210). Rather, it presupposes the union of man and God which is both intimately personal and profoundly universal:

A force which can move a mountain must be equal to that which piled it up. Therefore, the faith which can move mountains can neither be an intellectual opinion nor a personal feeling, no matter how intense. It must be the product of the union of the thinking, feeling and desiring human being with cosmic being—with God. The faith which moves mountains is therefore complete union— even if only for an instant —of man and God.

This is why illusion can in no way engender faith; and this is also why miracles due to faith are testimonies of the truth— and not only of sincerity —of belief, confidence and hope of the person through whom they are operated (210).

He goes on to conclude that…

“[Faith] is therefore neither logical certainty, nor the certainty of authority, nor the acceptance of a testimony worthy of faith—it is the union of the soul with God, attained through effort of thought, through confidence in that which is worthy of confidence, through accepting testimonies worthy of faith, through prayer, meditation, contemplation, through practising moral endeavour, and through many other ways and endeavours which help the soul to open to the divine breath. Faith is divine breath in the soul, just as hope is divine light and love is divine fire in the soul (210-211).

Empirical science, on the other hand, requires doubt. And yet, paradoxically, it requires faith, as well. On the one hand, empirical science doubts superficial experience, opinions, and tradition, but on the other hand, it believes in the possibility of discovering the truth. Thus he writes:

Does doubt alone suffice for discoveries? Is it not necessary to believe in the possibility of such discoveries before one sets out on the route which leads to them? Evidently this is necessary. The father of empirical science is doubt and its mother is faith. It owes its fruitfulness to faith, just as it owes its motivating force to doubt. Just as there is “scientific doubt” underlying empirical science as a method, so there is a “scientific faith” which underlies science as the principle of its fruitfulness. Newton doubted the traditional theory of “gravity”, but he believed in the unity of the world, and therefore in cosmic analogy. This is why he could arrive at the cosmic law of gravitation in consequence of the fact of an apple falling from a tree. Doubt set his thought in motion; faith rendered it fruitful (211).

At this point (212), our anonymous author presents a 12 point scientific creed which he challenges us to compare, article by article, with the Christian Creed and which refelcts, he suggests, the worldly wisdom of an inverted tetragrammaton:

“The series HVHY means to say that nothing precedes matter; that nothing moves it; that it moves from itself; that mind is the child of matter; that evolution is matter which engenders mind; and that, lastly, mind, once born, is the activity of matter in evolution, which becomes conscious of itself and takes evolution in its hands. The inverted tetragrammaton is without doubt the formula-synthesis of empirical science.

“Is it that of chaos and irrationality?

“No. It is the mirroring of the formula spirit-matter-evolution-individuality of the sacred name YHVH. It is not the formula of irrationality, no more than it is that of intelligence —it is the formula of cunning (“ruse”), i.e. of reflected intelligence” (213).

The fruit of the knowledge of good and evil, he goes on to argue, by reducing quality to quantity, does in fact open our eyes on the horizontal plane, giving us a significant degree of control over our natural environment. But this measure of control comes at price, namely the obscuration of the vertical dimension and the qualitative aspect:

“Does [the promise of the serpent] deceive us? No. It opens our eyes in fact, and thanks to it we see more in the horizontal; it gives us power over Nature in fact, and makes us sovereign over Nature; it is useful to us in fact, no matter whether for good or for evil. Empirical science in no way deceives us. The serpent has not lied — on the plane where its voice and promise were audible.

“On the plane of horizontal expansion (“the fields” of Genesis) the serpent certainly keeps its promise . . . but at what price with regard to other planes, and with regard to the vertical?

“What is the price of scientific enlightenment, this “opening of the eyes” in the horizontal, i.e. for the quantitative aspect of the world? It is at the price of the obscuration of its qualitative aspect. The more one has “open eyes” for quantity, the more one becomes blind to quality. Yet all that one understands by “spiritual world” is only quality, and all experience of the spiritual world is due to “eyes that are open” for quality, for the vertical aspect of the world. Thus number has only a qualitative meaning in the spiritual world. “One” signifies unity, “two”—duality, “three”—trinity, and “four”—the duality of dualities. The vertical world, the spiritual world, is that of values and, as the “value of values” is the individual being, it is a world of individual beings or entities. Angels, Archangels, Principalities, Powers, Virtues, Dominions, Thrones. Cherubim and Seraphim are so many individualised values or entities. And the supreme value is the supreme Entity—God” (214).

The solution to the Faith-Empirical Science antinomy, however, is not to abandoned empirical science, per se, but to realize it’s one-sided and (ultimately) subordinate nature. In other words, while the scientific creed is not The Truth, it may, in good conscience, be retained as method (215). Construed as method, it becomes rightly subordinate to Faith–NOT to “faith” understood as submission to the dead letter of dogmatic pronouncements, but to living Faith which is, among other things, “the voice of the presence of truth” (221). But how and where are we to encounter the voice of this living presence? How are we to recognize it? As indicated above,

“[Faith] is the union of the soul with God . . . Faith is divine breath in the soul . . . (211).

And one of the many “ways and endeavours which help the soul to open to the divine breath” (referred to in the extended quote, above) is to practice the spiritual exercise of The Hermit who, “clothed in the habit of faith and whose doubt fathoms the ground”, is able to draw light from darkness (217).

The Hermit as a Spiritual Exercise and the Gift of Black Perfection

- Drawing Light from Darkness [217-218]

The antinomies presented above offer examples of a thesis juxtaposed to its antithesis as clearly as possible — “as crystalized light” — beyond them only darkness:

“You will then arrive at a state of mind in which all that you know and clearly perceive is put into the thesis and its antithesis, so that they may be like two rays of light, whilst your mind itself is plunged into darkness. You know and see nothing more than the light of these two contrary theses; beyond them there remains only darkness. And it is then that one undertakes the essential thing about this exercise, namely the endeavour to draw light from darkness, i.e. an effort aiming at knowledge which appears to you to be not only unknown but also unknowable” (217).

- The Neutralization of Binaries [218]

After providing some historical context with respect to the method of the neutralization of binaries– i.e. the discovery of a third or “neutral” term corresponding to a given pair of terms designated as “active” and “passive” principles —our anonymous author presents three different ways of that such binaries can be neutralized:

- Above (synthesis on a higher plane)

- Horizontal (compromise on the same plane)

- Below (mixture on a lower plane)

- William Ostwald’s “Colored Body” [219]

As an illustration of the three different ways that binaries can be neutralized, our anonymous author discusses William Ostwald’s “Colored Body” which is formed by two identical cones fitted base to base to form an “equator” situate between the two points or “poles” of the resulting body:

As an illustration of the neutralization of binaries, discussed above, consider the following:

- The North Pole OR White Point is the synthesis of all colors (neutralization above).

- The Equator OR Points of Maximum Differentiation marking the transition between colors (horizontal neutralization).

- The South Pole OR Black Point is the confusion of all colors (neutralization below).

- Three Methods of Neutralization [219-220]

The discussion of Ostwald’s “Colored Body” suggests, by analogy, three methods of neutralizing binaries:

- The North Pole of Wisdom construed as the synthesis of the Equator of human knowledge (the South Pole being ignorance).

- The color Green (for example) as the mid-point between yellow and blue on the Equator.

- Beneath the Equator, the distinction between yellow and blue is gradually lost as one moves toward the South Pole.

Following this pattern, our anonymous author offers three possible accounts as to the relationship between Mathematics and the phenomenal world:

If we now take instead of the binary “yellow—blue” that of “mathematics — descriptive science” or “mathematics —phenomenalism”, and apply the three methods of “neutralisation” here, we obtain a formula of transcendental synthesis, another that is a compromise or equilibrium, and a third that is indifferent, as follows:

1. Transcendental synthesis: “God geometrises: numbers are the creators of phenomena” (the formula of Plato and the Pythagoreans);

2. Equilibrium: “The world is order, i.e. phenomena display limits due to the equilibrium that we call measure, number and weight” (the formula of Aristotle and the Peripatetics);

3. Indifference: “Our mind reduces phenomena to numbers so as to make it easier for the work of the mind to handle them” (formula of the sceptics).

We see, therefore, that Platonism is orientated towards the “white point” of wisdom, Aristotelianism moves in the “equatorial” region of precise distinctions, and scepticism tends towards the “black point” of nihilism (220).

- The Hermit as Prudence [220-223]

According to our anonymous author, “the traditional interpretation of the ninth Arcanum is prudence”–this is because . . .

“…the Hermit holds the lamp which represents the “luminous point” of transcendental synthesis; he is wrapped in a mantle, hanging in folds, for deploying the particular qualities which have their place in the region of the ‘equator’; and he supports himself with a staff for feeling his way in the domain of darkness, in the region of the reversed cone culminating in the ‘black point’. He is therefore a Peripatetic Platonist (en route around the ‘equator’), making use of scepticism (his ‘staff’) while he walks” (220).

Thus, the Hermit is constantly aware of being between “two darknesses” — that of “the white point” of absolute (transcental) synthesis, above (represented by his lamp); and that of subconscious, below–“the region of the reversed cone” of darkness which he explores with his staff (220). As such, he makes his way “from one particular color to another” in the equatorial region between these two darknesses (221). His mantle represents a kind of background knowledge of all the particular standpoints which he encounters between these two darknesses–a mantle which is open at the front to make room for the use of his lamp and staff (221). Through the gift of black perfection– which he practices in solitude –the Hermit is able to resolve apparent contradictions and arrive at a synthesis of antinomies:

“The Hermit is the spiritual image of he who follows the method and exercises the faculty of the ‘gift of black perfection’ (or the “gift of Perfect Night”). As this method comprises true impartiality, i.e. the search for the synthesis of antinomies and the third term of binaries, the Hermeticist must necessarily be solitary, i.e. a hermit. Solitude is the method itself of Hermeticism. For one has to be profoundly alone in order to be able to exercise the “gift of Perfect Night” in the face of contraries, binaries, antinomies and parts which divide and rend the world of truth” (222).

- Unity in Diversity (Rainbow Peace) [223-225]

Indeed, it is by virtue his solitary gift and method that the Hermit is also a peacemaker:

“He makes his way from opinion to opinion, from belief to belief, from experience to experience — and traces his route so that he traverses the way of peace between opinions, beliefs and experiences, being always equipped with his mantle, lamp and staff. He does so alone, because he walks (and no one can walk for him) and because his work is peace (which is prudence, and therefore solitude). [223]

And the sign of peace, we are told, is the rainbow where a perfect balance is achieved between unity and diversity:

“Peace is unity in diversity. There is no peace where there is no diversity, and there is no peace when there is only diversity. Now, unity where diversity disappears is not peace. For this reason, although the ‘white point’ of the coloured body, where all colours are drowned in light, is certainly that which renders peace possible, it is not peace as such, taken by itself. Similarly, the “black point” of the body, where all colours disappear into darkness, is not the point of peace, out rather the point of death of diversity and the conflicts that diversity can produce. It is therefore the ‘equator of living colours’ which is the region proper to peace. The living colours of the rainbow that appear in the sky are the visible manifestation of the idea of peace, because the rainbow causes us to see unity in the diversity of colours. There the whole family of colours presents itself to us as seven sisters who join their hands. For this reason the rainbow is the sign of peace (or alliance) between heaven and earth…” (223-224).

Contemplation/Action [225- 226]

Several times throughout these meditations, our anonymous author distinguishes between a more profound, authentic designation, which is capitalized, and a more superficial, inauthentic designation, which is printed in all lower case letters (e.g. Triumpher & triumpher in Letter 7, page 164-165 OR Art & art in Letter 22, page 629). Likewise in this section, perhaps, we might do well– on our own initiative –to distinguish between Contemplation and contemplation (the latter indicating a hedonistic indulgence in various currents of theological and mystical thought; and the former indicating authentic Contemplation which, in the final analysis, is inseparable from authentic action). With this distinction in mind, we can more easily explicate his discussion of the “practical antinomy” which he variously formulates,

- “wisdom — will”

- “universal synthesis — particular action”

- “knowledge — will”

“To become contemplative”, he writes, “is to turn to inactivity. To become active is, in the last analysis, to turn to ignorance” (225). Those who exemplify the first extreme are said to prefer “enjoyment” over “effort”, while those who exemplify the second extreme will suffer from “narrow mindedness” (225, 226).

Early on, he compares the life of these “so-called contemplatives” (of the first extreme) to that of passengers on a cruise:

“A boat carries passengers and a crew consisting of a captain, officers and sailors. It is the same with the boat as with human society, which voyages from century to century. The latter also bears crew and passengers. The members of crew are vigilant so that the boat follows its route and the passengers are healthy and safe. Now, to take the part of living a contemplative life implies the decision to become a passenger on the boat of human society and to leave the responsibility for the boat’s route, and for the well-being of the other passengers as well as oneself, to the crew—the captain, and the officers and sailors. One therefore becomes a passenger on the boat of human history, when one chooses a life of the contemplative kind. This is the moral price of this choice” (225).

A bit later he writes,

“…choosing the pole of contemplation at the expense of the pole of will within the human being means that one prefers the enjoyment of contemplation to the effort of will and action (spiritual or outward) that the latter entails (225).

This paragraph brings to mind another in Letter 22:

“The Arcanum “The World” thus communicates to us a teaching of immense practical sigificance: “The world is a work of art. It is animated by creative joy. The wisdom that it reveals is joyous wisdom . . . Happy is he who seeks wisdom in the first place, for he will find that wisdom is joyous! Unhappy is the one who seeks the joy of joyous wisdom in the first place, for he will fall prey to illusions! Seek first the creative wisdom of the world —and the joy of creativity will be given to you in addition (644)”

Indeed, this text would seem to confirm that (authentic) Contemplation of (authentic) Wisdom is intrinsically active/creative. And it is just this kind of contemplative/active life that the Hermit embodies:

“The Hermit is neither deep in meditation or study nor is he engaged in work or action. He is walking. This means to say that he manifests a third state beyond that of contemplation and action. . . . the term of synthesis, namely that of heart. For it is the heart where contemplation and action are united, where knowledge becomes will and where will becomes knowledge. The heart does not need to forget all contemplation in order to act, and does not need to suppress all action in order to contemplate. It is the heart which is simultaneously active and contemplative, untiringly and unceasingly. It walks. It walks day and night, and we listen day and night to the steps of its incessant walking. This is why, if we want to represent a man who lives the law of the heart, who is centred in the heart and is a visible expression of the heart — the “wise and good father”, or the Hermit — we present him as walking, steadily and without haste” (226).

Thus, he concludes, “the heart is the solution” to the practical antinomy of “knowledge – will” or “contemplation – action” (226).

[Editor’s Note: Follow these links for additional insight into the relationship between Contemplation and Action (Rene Guenon) AND The Intellect and the Heart (Martin Lings).]

- Elaboration on the Lotus Centers and the Christian Mantras which relate to them with a continued emphasis on the heart… [226-228]

The “heart” that we have in mind here is not that of emotion and the faculty of being passionate that one generally understands by “heart”. It is the middle centre of the seven centres of man’s psychic and vital constitution. It is the ” twelve-petalled lotus” or anahata centre of Indian esotericism. This centre is the most human of all the centres of “lotus flowers” (226).

The heart is the solution to most all our dilemmas, it seems, because…

The heart itself . . . which alone of the centres is not attached to the organism, and which can go out of it and live . . . with and in others, will become a traveller, a visitor and anonymous companion of those who are in prison, those who are in exile, and those who bear heavy loads of responsibility. It will be an itinerant Hermit, traversing ways leading from one end of the earth to the other, and also ways through spheres of the spiritual world—from purgatory to the very feet of the Father. Because no distance is insurmountable for love and no door can prevent it from entering—according to the promise which says: “and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matthew xvi, 18). It is the heart which is the marvellous organ called to serve love in its works. It is the structure of the heart— simultaneously human and divine, a structure of love —which by way of analogy can open our understanding to the significance of the meaning of the following words of the Master: “And lo, I am with you always, to the end of time” (Matthew xxviii, 20).

He concludes this section by relating the following “Christian formulae” or “mantras” to the traditional lotus centers:

-

- I am the resurrection and the life – the eight-petalled lotus

(crown center — revelation of wisdom) - I am the light of the world — the two-petalled lotus

(between the eyebrows — intellectual initiative) - I am the good shepherd — the sixteen-petalled lotus

(larynx center — the creative word) - I am the bread of life — the twelve-petalled lotus

(heart center — love) - I am the door – the ten-petalled lotus

(umbilical center — science) - I am the way, the truth and the life — the six-petalled lotus

(pelvic center — harmony & health) - I am the true vine — the four-petalled lotus

(base of the spine — creative force)

- I am the resurrection and the life – the eight-petalled lotus

Meditating on these Christian mantras, he suggests, does not merely awaken the centers as they are, but transforms them “in conformity to their Divine-human prototypes” (228).

- The Supremacy of the Heart [228-229]

The supremacy of the heart is emphasized once again in these closing paragraphs:

“Now, the distinctly practical teaching of the ninth Arcanum is that it is necessary to subordinate the directing intellectual initiative, as well as the flowing spontaneous movement of thought, to the “heart of thought”, i.e. to the profound feeling that is found at the basis of the thinking that one sometimes designates “intellectual intuition” and which is the “feeling for truth”. It is also necessary to subordinate both spontaneous imagination and actively directed imagination to the direction of the heart, i.e. to the profound feeling of moral warmth that one sometimes designates “moral intuition” and which is the “feeling for beauty”. Lastly, it is necessary to subordinate spontaneous impulses and designs directed from the will to the profound feeling which accompanies them that one sometimes designates “practical intuition” and which is the “feeling for the good” (228-229).

In short . . .

The Hermit of the ninth Card is the Christian Hermeticist, who represents

. . . the “work of salvation”— because the “salvation of the soul” is the restoration of the reign of the heart (229).

With the restoration of the reign of the heart, the development of conscience and the growth of freedom (referred to at the end of Letter 8) is complete.

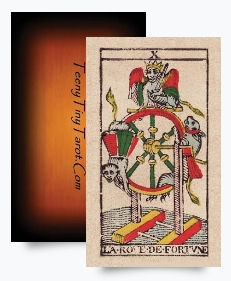

MOTT Study Guides –> X. The Wheel of Fortune